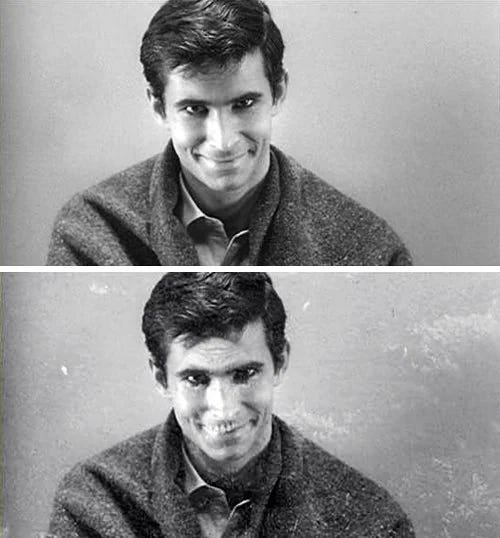

The first time we see Longlegs, and Nicolas Cage as Longlegs, we don’t see him. Not all of him, anyway. Not enough to remember him, to pick him out of a lineup. It is the winter of 1974, and young Lee Harker—almost 9 years old—sees a car stop on the street outside her house, situated off a rural county road. She steps out of her house, tiptoes around to the back, and then, with the sting of strings on the soundtrack, sees him: Longlegs. Part of him. The camera angle cuts off the upper half of Longlegs’ face, so that we only see his mouth moving as he speaks. Indeed, when he lowers himself down into Lee’s line of sight, claiming that he “wore his long legs” today, the scene cuts, and we’re into the credits, the merest glimpse of Longlegs’ face smeared in our memories.

This feels like movie trickery. The jumpscare, the quick cut—these are the tools at the disposal of the horror filmmaker, to make the audience jump in their seats. I sure did, when I saw it in the theater. But we are seeing far more than this, far more than we realize. We are seeing how Lee’s memory works—or rather, how it doesn’t. We see that when she has the chance to look upon the killer’s face, to hold it in her memory, her memory instead refuses. It will not, under any circumstances, recall this man.

We are also, at a higher, or perhaps deeper, level, seeing the mind of the movie itself. Longlegs gives us a world where no one, not even the creator himself, can bring himself to look reality in the face. One can only glimpse it, out of the corner of one’s eye, in moments that one struggles to recall afterwards. Some movies feature recovered memories as a plot point; Longlegs, the movie itself, is a recovered memory, one imprinted upon our own memories through our eyes. And like a recovered memory, it doesn’t tell the whole story. It leaves out as much as it contains. That’s where we have to find what’s missing.

Here is the basic storyline of Longlegs, as it’s generally understood.

FBI Agent Lee Harker, thanks to her display of possibly-psychic powers, gets assigned to investigate a series of brutal serial murders. Families, murdered in their own homes, in which a letter is always found, signed by LONGLEGS. Only, technically, Longlegs, whoever he is, doesn’t appear to be the one who commits the murders. Instead, the father of each family suffers a break of some kind, and kills his family in a rage, then kills himself. In his letters, Longlegs claims responsibility, but the FBI cannot yet determine how he manages to kill the families. He doesn’t even seem to be present at the time of the murders.

Lee dives into the case with gusto. She works the ciphers, she lays out maps. She also receives some help from Longlegs himself, who sneaks into her home and leaves a birthday card for her. She uses the note in the card to decode Longlegs’ letters, and which also leads her to discover the algorithm he uses to select his victims. Young girls with birthdays on or around the 14th of a given month, which, when plotted out on a calendar, describe a triangular figure associated with Satanism.

One of the clues leads them back to an earlier victim of Longlegs, a young girl whose family was killed while she herself was spared, for reasons unclear. Lee and her boss investigate the woman’s home, and in the barn, they discover a doll. A life-size doll, the size of a young girl, with remarkably detailed features. Contained in the doll’s head is a metal sphere of some sort, a brain-ball, whose purpose seems unclear.

Lee’s boss tells her something about her own past, something she’s forgotten. On her birthday in 1974–the 14th, at that–her mother made a call to the police regarding an intruder. Lee has no memory of this. She visits her mother at home, finding her speaking in riddles. She looks in her childhood dresser and discovers a series of Polaroids—including one of Longlegs himself. This is the photo she took as a child, which she seemingly forgot until now.

The photo is used to put out an APD for Longlegs. He is captured almost immediately, waiting at a bus stop on a rural road. Almost as if he’s waiting to be caught. Lee becomes convinced that Longlegs had an accomplice. She fears her own mother may have been involved somehow. She interviews Longlegs, but before she can get him to say anything, he kills himself by slamming his face repeatedly into the table, his nose shattering.1

Lee goes to her mother’s house, where her mother, dressed as a nun, shoots and kills the FBI agent who drove Lee there. She also shoots a doll of young Lee, much like the one found in the barn. This causes Lee to faint, and to recall more of the past than she has before. In 1974, Longlegs came to kill Lee and her mother, but her mother made a deal. She would help Longlegs kill the families, and she would do by posing as a nun and bringing gifts to the families—the dolls. Longlegs is a master dollmaker, crafting them in Lee’s basement all along. The brain-ball in the dolls causes the families to go berserk, casting them in a trance, resulting in their deaths. Lee’s mother did all of this, she says, to save Lee.

Now Lee’s mother is going to Lee’s boss’s house, where his daughter is having a birthday party. She too brings a doll, which casts the family into a trance. The boss kills his wife, then Lee shoots him. She also shoots her own mother, to stop her from harming the daughter. She tries to shoot the doll, to destroy the brain-ball within, but her gun is out of bullets. The film ends as Longlegs appears to declare, “Hail Satan!” followed by T. Rex over the closing credits.

Now, the most straightforward explanation for what’s going on here is that, as Longlegs himself claims, he is doing the work of the Devil. He worships Satan, and the demonic power he wields is what enables him to make the evil dolls, which make the families tear themselves apart. There is an abundance of evidence in the film as well, as in a series of shots where a devil-like figure, with horns and all, hovers in the background like an evil Where’s Waldo. The filmmaker himself, Osgood Perkins, has even stated that the Devil is an active presence in the story.2

Here’s the thing, though: I do not buy this for a second.

The devil, in Longlegs, is a red herring. There are no demonic or satanic forces at play whatsoever. There are supernatural forces at work, but they’re different than what we’re led to believe. This is not a story of the devil making you do it. This is a story of what we do ourselves, and what we make ourselves forget.

The key here is to realize that Lee knows far, far more about what has been going on in her presence than she lets herself realize. You get the sense of this when, after her mother has destroyed the doll, Lee wakes up in the basement of her house—the very basement where Longlegs has hid all these years, after making the deal with her mother. See how familiarly she moves through this space. She has been here before. She knows where to go. This is because she is far more pivotal to the designs of Longlegs, and her mother, than she has let herself know.

Here is where I make a big leap: the power that Longlegs places in the brain-balls of the dolls does not come from the Devil. It comes, rather, from inside the house. It comes from Lee.

Recall the beginning of the movie, where Lee senses the presence of a killer in a house through psychic means. Recall the test she takes at the FBI’s behest, and how this is mostly forgotten for the rest of the movie. The FBI fails to capitalize on Lee’s psychic abilities, and where they fail, Longlegs succeeds.

Since she was a girl, and since he began living in the family basement, Longlegs has been siphoning Lee’s psychic powers, and placing them in the brain-balls of the dolls. The dolls are then brought into the families’ homes by Lee’s mother, where they proceed to do their dastardly work. The father in each home is driven mad, becoming the family annihilator of tabloid lore, once Lee’s psychic powers are fed into him. For Lee herself harbors intense enmity toward her own father, who’s been absent her whole life, and Longlegs, acting as a kind of surrogate father, nurtures that anger, bringing it to its fullest expression. Her father, as we will later see, is a killer too. The fathers of the families are remade as killers in his image.

Lee, her mother, and Longlegs—a makeshift family whose means of staying intact is the ritualistic destruction of all other families.

This raises a question, though. Who is Lee’s father? Did he do something awful to her, that results in her anger? Or did his leaving the family when she was young enrage her to this point of psychic murder?

The obvious answer would be to say that Longlegs is her father, that she carries the same murderousness that he harbors. But I don’t think there’s any evidence in the movie to suggest this. If anything, the movie deliberately gives nothing that would even suggest this reading, which is the right call. Having Lee’s father turn out to be Longlegs would feel very literal and obvious, and the strange power of Longlegs lies in how different characters keep playing the roles that aren’t meant for them–Lee’s boss as Lee’s father, the dolls as sisters. Something so literal, so genetic, as stating that Longlegs is Lee’s biological father would feel off in such a scheme.

Really, the film works very hard to deny us any information whatsoever as to who Lee’s father might be. This is narrative design, yes, but this is also a further example of the repression that exemplifies this entire story, from the characters to the one who created them. No one wants to admit anything to themselves.

I think I know who Lee’s father is, though. It is perhaps even more outlandish, but I think it fits. Before we reach that notion, however, we must take a detour into the filmmaker himself, Osgood Perkins. For Longlegs isn’t just a horror movie; it is an autobiography, a work of autofiction as much as any Karl Ove Knausgaard novel.

Osgood Perkins, like Nicolas Cage, could be called a nepo baby. His father was actor Anthony Perkins, and his mother was a photographer named Berry Berenson. Anthony Perkins was most famous, of course, for playing Norman Bates in Psycho, one of the landmark characters in the annals of horror film. Osgood was well aware of his father’s fame for this role; indeed, he played a part in it. In Psycho II (1983), he played the young Norman Bates in a series of flashbacks.

For all of his father’s fame, though, there was one part of his father’s life he was not aware of. A part that his parents worked very, very hard to keep secret. Anthony Perkins was gay. He lived the life of a gay man in the Hollywood and New York of the 1960 and 70s, though he never went public with any of this. Eventually, he met a woman named Berry Berenson, who was a fashion photographer. They married, and she convinced her husband to undergo a kind of conversion therapy, in the hope that he could live the normal life of a straight, married man.

Yet that never really took, and Perkins continued a very shielded, secretive life as a gay man throughout his marriage, which his wife was aware of. Yet this fact was kept from Osgood Perkins throughout his life, and it was his mother who kept that from him.

Perkins died in 1992 of AIDS-related causes, though Osgood wasn’t fully aware of that fact at the time of his father’s death. Nine years, his mother would die on September 11, 2001. She was aboard American Airlines Flight 11, which crashed into the North Tower of the World Trade Center.

With a personal history like that, is it any wonder that Osgood Perkins would look to the horror genre to express the feelings he’s lived with his whole life? His biography is a kind of Hollywood Gothic, featuring closeted fathers, tragic deaths, and mothers keeping secrets from their sons.

Watching Longlegs, you realize that the title is misleading, deliberately so. The true antagonist of the film is not Longlegs; it is Lee’s mother, Ruth, played by Alicia Witt. She is the one who’s been working so hard to keep this secret from Lee, tampering with her daughter’s memory in the effort to give her a shot at a normal life. “You got to grow up!” her mother says to Lee, when Lee pleads with her, asking how she could do this. But Lee never had a chance at normalcy. She was doomed from the start.

Longlegs, then, is a kind of autofictional horror, where the circumstances and especially the emotions of Osgood Perkins are translated into this heightened, gothic, genre register, where houses are built on secrets, and revealing them causes the foundations to crumble. In fact, that history is written into the film itself, into the story, at a level one can’t quite detect, but can surely sense, at the level of dread.

So who is Lee’s father? What genetic history has been passed onto her, that a serial killer preys upon her psychic abilities to accomplish his dark aims?

We know that already. We have seen Lee’s father before, albeit in a different movie. A movie that broke the ground where the house of Longlegs was built.

Lee’s father, you see, is Norman Bates, from Psycho.

Yes, this is where I really jump the shark.

As outlandish as this may sound, though, the circumstances of the film do make it possible. Lee Harker, in January of 1974, is about to turn nine years old. This means she was born in 1965, and conceived the previous year.

Psycho takes place in 1960. At the end of film, Norman Bates, his pathology as his mother’s killer revealed, where the personality of his dead mother has overtaken his own, is placed in a mental institution. He will remain there for 22 years, until he is released in the early 1980s, as portrayed in Psycho II. That would make it rather difficult for anyone to gain access to him, and have him father a child.

But do you know who would have access? A nurse. And Lee’s mother, as she reminds her multiple times, worked as a nurse for eight years. Those eight years sync up perfectly with the period of Norman Bates institutionalization, and with the birth of Lee Harker.

At some point, compelled by the strange man who spoke in the voice of his mother, Ruth Harker became pregnant with Norman Bates’ child—a girl, as it turned out. Some residue of her father’s damaged psyche was passed onto Lee, resulting in her psychic abilities. And her mother, already accustomed to conversing with psychopaths, was able to convince Longlegs to spare the life of her child, in exchange for helping him carry out his dark aims. And Longlegs himself found himself with the perfect tool to carry out those aims. Not the devil, but the vengeance of a young girl who never knew her father, and never came to terms with the darkness she carried within her. Longlegs captured that darkness, and transformed normal father into facsimiles of Norman Bates, killing the ones they claim to love.

Longlegs, then, is the story of Osgood Perkins creating a cinematic half-sister for himself, almost like Longlegs creates his dolls. Regenerations and reiterations, all of them leading back to the dark basement of an empty house.

Almost like a doll, the shattered face of a broken china doll.

Much like his earlier film, The Blackcoat’s Daughter, which I also recommend. The Devil is very much real in that story, by the way, which is partly why figuring out what’s going on in Longlegs is so tricky.