Earlier this week, I posted the third episode of my novella, The Unauthorized Guide to MindShifter. All eight episodes will go live every Thursday throughout Substack Summer, leading up to the thrilling SEASON FINALE!

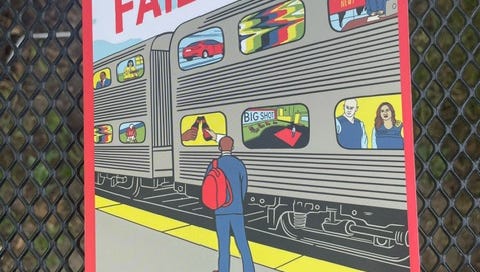

Each Sunday during the serialization process, I’m posting an essay that’s about TV in one way or another. This week, I am writing about True Failure, Alex Higley’s recent novel, which is about reality TV. Plus some stuff on how I’m a big fat liar.

Why does a man lie? To get something he wants? To avoid something he doesn’t want? To wield power just for the sake of wielding it?

Or—just to see what it feels like? To hide something from everyone, including yourself?

Alex Higley’s True Failure is about a man who tells a lie.1 A lie of omission, perhaps. Ben lives in Chicago and works an office job. He gets fired on the first page—the first sentence, even: “Ben received a small severance package.” He goes home. But, he doesn’t tell his wife that he got fired. He doesn’t tell her anything He still gets up every morning and “heads out” as if to work, but he just goes to the library.

Okay, that last part crosses into active lying territory, I think we can all agree.

What does Ben do at the library? Two things: he watches Law & Order: Special Victims Unit2 on his laptop, becoming obsessed with Mariska Hargitay; and he hatches a plan to get on TV himself.

Big Shot is a reality competition show wherein would-be entrepreneurs pitch their ideas to ‘big shots’ from the business world, in the hope they can receive seed money to get their own business off the ground. Familiar, for sure. So much so that Ben comes up with a rather mediocre idea, yet also becomes convinced that he can get on the show—that he can win, even.

So maybe he’s not just lying to his wife.

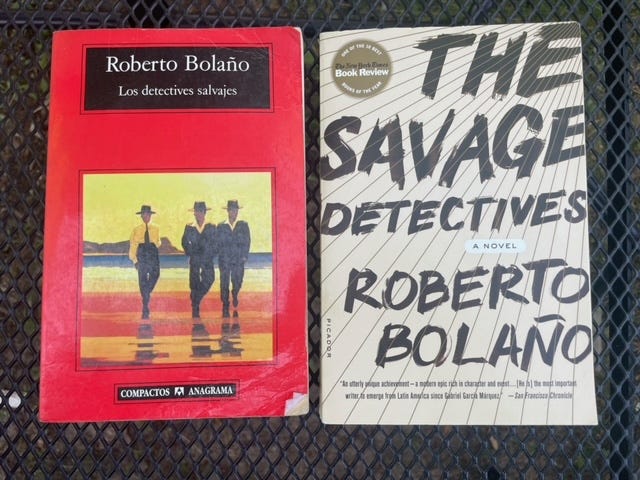

In 2007, I went to Chile. Moved, perhaps, would be the word. I had bought and open-ended plane ticket to Santiago so I could live there and teach English as a foreign language down there. And I did. I taught at a language school, I gave private lessons to bankers in their offices, I landed a gig with the Chilean navy teaching officers. (One guy honed his English by telling me about his adventures in the fleshpots of Bangkok. It was like a choppy audiobook of a Michel Houellebecq novel.) It was at the latter gig that I told a wildly incommensurate lie.

I signed a contract that placed me at the school for six months. After that, I planned to return home. A solid year in Chile, teaching English and learning how to get by in Spanish. I even read Bolaño in the original.

Before my contract was over, though, I found I had made a mistake in my airplane ticket. It was not open-ended like I had thought. I had to leave within a year of me buying the ticket—and that window was about to close. Like, within a week. If I didn’t, I’d have to buy a whole new ticket, for something in the neighborhood of $3000. More than I could afford.

I could have told my employers that I needed to leave right then. Explain the situation. They might have been unhappy, sure. But they couldn’t stop me.

But the thought of explaining all that felt insurmountable, somehow. So I didn’t. Instead, I lied.

Ben’s idea for Big Shot is this: he wants to create a local version of Big Shot for regional markets, like where he lives in Chicago. He wants to franchise the show. He records an audition tape of himself presenting the idea.

He knows it’s lame. He sees that. Yet he hopes that viewers can see his lameness and long to forgive it, like they want to forgive themselves.

He finds a sympathetic ear. A producer on the show, who has an eye for these left-field human interest types, takes a liking to Ben. She fast-tracks his audition. She flies him out to Los Angeles, to the Big Shot studio.

Of course it goes horribly.

Here is the lie I told.

Instead of explaining that I needed to leave early because my plane ticket was about to expire, I told my boss that my father was sick. Very sick. Stomach cancer. And that I needed to return home immediately.

My father was not sick, of course. But I landed on this lie as it felt clear, and gave me a clear reason for leaving.

And you know what: it worked. They believed me. They let me end my contract early, no problem. They even got me a cake for a going-away party.

People want to believe you. It’s easier that way.

But why did I choose to lie so boldly rather than explain the truth? Because I was embarrassed. Like a good Midwesterner, I lied to spare myself shame.

Ben’s wife figures out fairly quick that he’s no longer going to work. Yet she doesn’t confront him, either. For his charade to come to light, Ben has to travel all the way to LA, to confess to the cameras before the big shots. He’s a Midwesterner too.

Me, I just need a newsletter to spill my guts.

Higley is a straight white male and True Failure literary fiction. But wait, I thought books like that didn’t get published anymore? Granted, it’s on a small press (the mighty Coffee House Press, publisher of, among many others, my own personal guiding star, Brian Evenson) rather than a Big 5. But still! A novel about heterosexual masculinity: they exist, folks.

What is it about literary authors and SVU? Her Body and Other Parties Carmen Maria Machado contains a novella about the show. Which is only two examples, I suppose. Not quite a trendpiece, which requires three examples. Still, notable.